Reading Emily Dickinson

And softly thro' the altered air

Higgledy piggledy

Emily Dickinson

Wasn’t, while living, a

Popular name:

Hiding away, she was

Writing herself into

Agoraphobically

Posthumous fame.

“Occasionally when students tell me it’s hard to know how to read the poems,” writes Brenda Hillman in the introduction to The Pocket Emily Dickinson, foreshadowing some of my reactions, “I tell them, read them quickly and let them shock you. If a line stays, read it again until you feel it is yours, and let the strange capital letters and the dashes carry the poems to the place in your unconscious that won’t worry what they mean.”

That is very generous; I would not have earned a B in Year 12 English1 without trying to understand what I was writing essays about.

Upon a single Wheel –

But I worry that Hillman over-estimates my reading comprehension compared to students who are studying poetry at tertiary level. When words don’t directly convey their meaning, my brain leaves a blank and I continue reading, often reaching the end of a poem without even a surface-level grasp of the content. When in high school English classes, the teacher would ask us what a particular line said, our resolute silence – mine at least – came from sincerely not being able to infer a meaning.

Eventually the teacher would explain it to us, sometimes persuasively. When recently I was reading some of Shakespeare’s sonnets – easier than Dickinson – I had to expend effort to make pieces fit together, but sonnet 116 was much easier, because I had studied it in Year 12. Long-remembered lessons gave it an immediate clarity (albeit still imperfect): I knew that a bark was a ship, the guiding [North] star used for navigation completing the metaphor.

But with The Pocket Emily Dickinson I was on my own with 114 unannotated poems, presented in an approximate chronological order (more than half are from c. 1862 to 1863). I would not read these quickly: the gains in understanding from a minimum of two careful reads per poem are substantial, and even then I often fail.

Within my Garden, rides a Bird

Upon a single Wheel –

Whose spokes a dizzy Music make

As ’twere a travelling Mill –He never stops, but slackens

Above the Ripest Rose –

Partakes without alighting

And praises as he goes,Till every spice is tasted –

And then his Fairy Gig

Reels in remoter atmospheres –

And I rejoin my Dog,

I was intrigued enough after my two reads to Google this poem, Dickinson blogger Susan Cornfeld telling me that the bird is a hummingbird – ah! I had just pictured… a bird… making noise? Flying from flower to flower? It feels obvious in hindsight that it’s a hummingbird and not a seagull, but I do not automatically infer this context, and I think that an ability to do this is part of what separates better students and readers of poetry from me.

Continuing:

And He and I, perplex us

If positive, ’twere we –

Is “He” the dog or the bird now? I start to flail.

Or bore the Garden in the Brain

The Curiosity –

Total blank.

But He, the best Logician,

Refers my clumsy eye –

To just vibrating Blossoms!

An Exquisite Reply!

Blank. But the exclamation marks let me share in the intended surprise at the conclusion; it is fun to let the words wash over me, comprehended or no. The old pronunciation of ‘exquisite’ has stress on the first syllable, so the final line is iambic, like all the others.

That blog post (same link as previous) explains that the second-last stanza is the poet expressing doubt about whether they had really witnessed the hummingbird or instead had imagined it (“bore the Garden in the Brain”); in the final stanza the dog points out still-vibrating flowers as evidence that the bird really had passed there. …Ah….

Perhaps I would do better to read an edition containing poems along with exposition. But even if I can enjoy a poem after being told what it means, I think that it would be unsatisfying to avoid the challenge of trying to get there alone.

My Life had stood – a Loaded Gun –

In Corners – till a Day

The Owner passed – identified –

And carried Me away –And now We roam in Sovereign Woods –

And now We hunt the Doe –

And every time I speak for Him –

The Mountains straight reply –

…

Though I than He – may longer live

He longer must – than I –

For I have but the power to kill,

Without – the power to die –

With moderate effort, I had concluded that this poem was written from the perspective of a gun and, satisfied with my analysis, I Googled. Cornfeld’s co-blogger Adam DeGraff writes that “There are as many interpretations of this poem as there are readers of it, and I recommend looking at several to get a feel for the possibilities.” Ah… the gun is supposed to be a metaphor. I do not automatically try to parse meaning in this way.

And on reflection I will stay true to my principles and not entertain such readings, Be Judgment – what it may. The gun is a gun, and the poem is a meditation on the nature of life and its taking by inanimate objects. Any poet who wants me to interpret a metaphor will need to make it clearer. “Hope” is the thing with feathers – / That perches in the soul –, now that’s a metaphor.

Tell all the Truth but tell it slant –

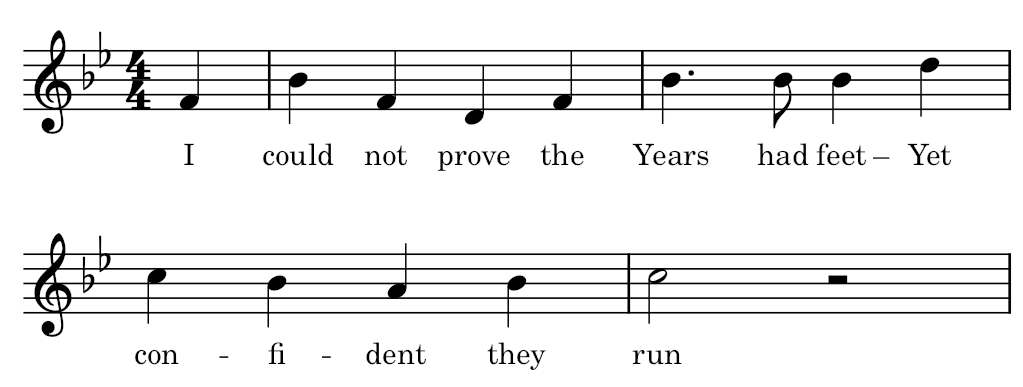

Most of these poems are written in, or almost in, common meter: alternating lines of iambic tetrameter and trimeter, the trimeter lines rhyming. One could, though one probably hasn’t, sing some of the poems to the tune of ‘Advance Australia Fair’.

Whether due to something inherent in the nature of the English language’s prosodic rhythm, and/or a contingent continued popularity through the centuries, it feels to me the easiest and most natural of meters. It is comfortingly familiar to read, even in its variations, and provides sonic enjoyment even when meanings remain obscure.

My first rhythmic unsettlements came not from dashes as I had expected – there aren’t many in the first few selected poems – but rather from imperfect rhymes, such as Gig and Dog or Doe and reply in the previous section. An early by and Victory pair could be chalked up as a poetic archaism recalling older pronunciations, but today and Victory?

What dignified Attendants!

What service when we pause!

How loyally at parting

Their hundred hats they raise!

I felt a non-randomness to these choices but I needed several examples to realise that Dickinson was rhyming only the line-ending consonants or their absence. I did not know that the term ‘slant rhyme’ extends to this practice; I had only encountered slant rhyme in the form used by today’s songwriters, in which the final vowels are rhymed but a line-ending consonant may vary – the usual effect is to give the listener’s brain a satisfying resolution that doesn’t draw attention to itself (there are counter-examples).

The consonant-only rhymes by contrast leave me feeling off-kilter; I have a sense of not-quite-resolution that interrupts me, pokes me in a new direction as I float above the text. Enough of Dickinson’s rhymes are perfect that I quickly settle back in to expecting them, ready to be lightly jolted anew.

I shall know why – when Time is over –

And I have ceased to wonder why –

Christ will explain each separate anguish

In the fair schoolroom of the sky –He will tell me what “Peter” promised –

And I – for wonder at his woe –

I shall forget the drop of Anguish –

That scalds me now – that scalds me now!

(The section title poem is perfectly rhymed.)

Hurries a timid leaf.

No lines in this collection carried themselves to a place in my unconscious more than the fourth tercet of this early poem of changing seasons, from c. 1859:

These are the days when Birds come back –

A very few – a Bird or two –

To take a backward look.These are the days when skies resume

The old – old sophistries of June –

A blue and gold mistake.Oh fraud that cannot cheat the Bee –

Almost thy plausibility

Induces my belief.Till ranks of seeds their witness bear –

And softly thro’ the altered air

Hurries a timid leaf.Oh Sacrament of summer days,

Oh Last Communion in the Haze –

Permit a child to join.Thy sacred emblems to partake –

Thy consecrated bread to take

And thine immortal wine!

As I reread this poem my feeling is of an unremarkable mild pleasantness, floating on a gentle uncertainty about which season is changing into which, before an explosion of colour, a swelling full-brain chorus of Till ranks of seeds their witness bear – continuing in perfect rhythm And softly thro’ the altered air. But once the leaf has timidly hurried away, the sound and light and colour recede.

I mean most of that description metaphorically, but the only thing I can liken the effect to is hearing Diana Deutsch’s ‘sometimes behave so strangely’ melody in the middle of ordinary speech; skip to 28:04 in this video if you don’t know what I’m referring to and want to:

I’ve turned those three lines over in my head many times,

Till ranks of seeds their witness bear –

And softly thro’ the altered air

Hurries a timid leaf.

much more often than the rest of the poem. They don’t appear to be especially popular lines, but something about them appealed to me on my first reading, and extensive repetition now makes them stand out all the more.

Occupying a similar prominence in my brain, and attendant intensity upon meeting it, is the only stanza of Dickinson’s that I was previously at all familiar with, thanks to xkcd.

(I gather that Dickinson is widely studied in American high schools, but she was not in my curriculum, which drew much more heavily from the Commonwealth than the US; for most of my life, I’ve known of Dickinson mostly as a reference in ‘The Dangling Conversation’.)

Because I could not stop for Death –

He kindly stopped for me –

The Carriage held but just Ourselves –

And Immortality.

I’m not sure if this stanza would stand out to me if I’d never seen it before – perhaps it is just recognition. But the internal (modern-style!) slant rhyme of held and ourselves makes it particularly pleasant to the ear, so I like to think that I would have noticed it anyway.

By the end of the poem,

Since then – ’tis Centuries – and yet

Feels shorter than the Day

I first surmised the Horses’ Heads

Were toward Eternity –

I’ve forgotten that a carriage in those days might be drawn by horses; she is in her funeral carriage; ah….

To Hands I cannot see –

There really are a lot of dashes in Dickinson’s poems; often they end a poem, giving an impression that the poem continues through time, never concluding.

In at least one case that I noticed, a dash introduces some metrical disorientation:

I reckon – when I count at all –

First – Poets – Then the Sun

First should be unstressed so that the second line is in iambic trimeter, but the dash that immediately follows it suggests that we start the line with two stressed syllables separated by a pause. Only after a first stagger through the punctuation do I go back and figure out the stress pattern.

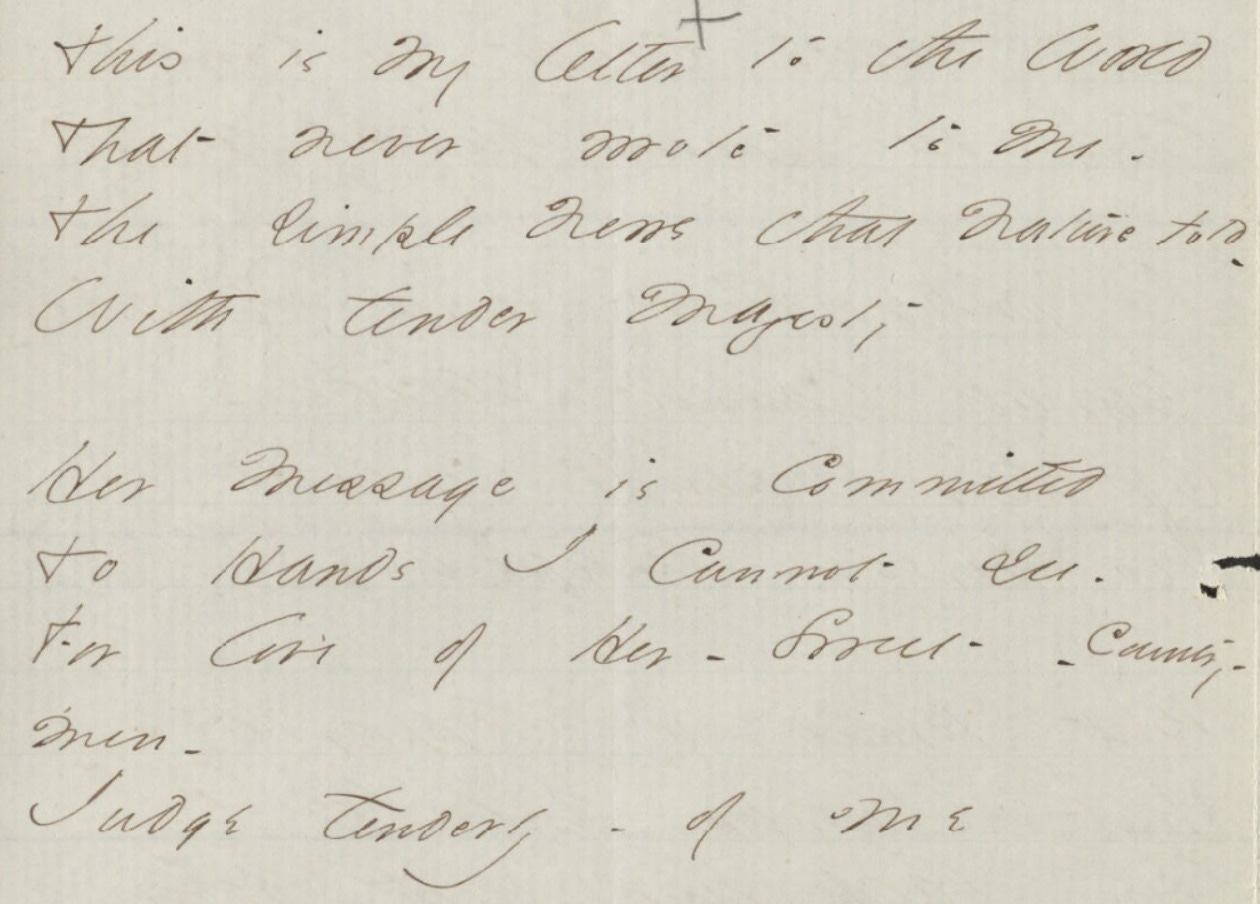

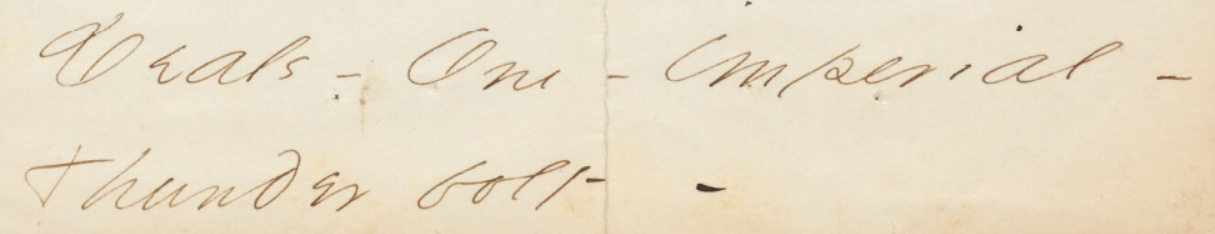

In The Pocket edition, the poems have en-dashes with a space on either side, in contrast to the introduction, which uses unspaced em-dashes. This editorial choice evidently relates to something in the handwritten manuscripts, so let us study some scans from the Emily Dickinson Archive.2

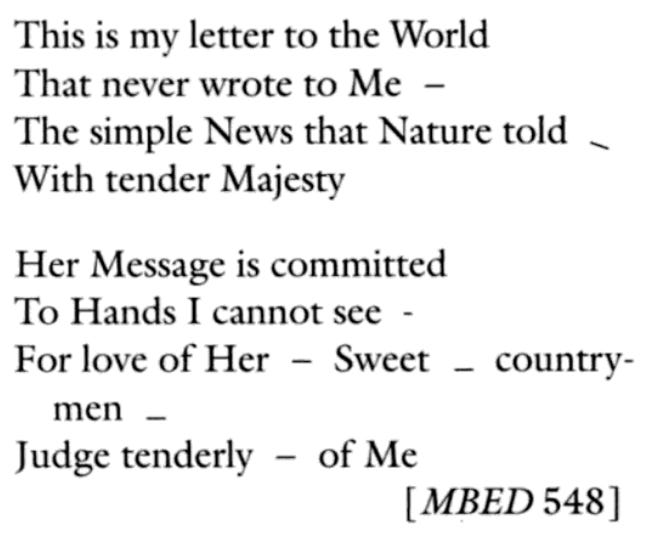

This is my letter to the World

That never wrote to Me –

The simple News that Nature told –

With tender MajestyHer Message is committed

To Hands I cannot see –

For love of Her – Sweet – countrymen –

Judge tenderly – of Me

Those are some small dashes! I can respect the choice of editors who use hyphens, maintaining something of the handwritten visual impression in the printed page. But editors would not (I assume!) feel a need to faithfully preserve Dickinson’s lower-case t’s, which often have cross and stem disconnected. I think that similarly, it is appropriate to use a standard modern glyph for her dashes, instead of trying to display handwriting particularities in print. As someone raised on spaced en-dashes, the Pocket choice is comfortable for me, even though I think it would make more sense for the publisher to use em-dahes.

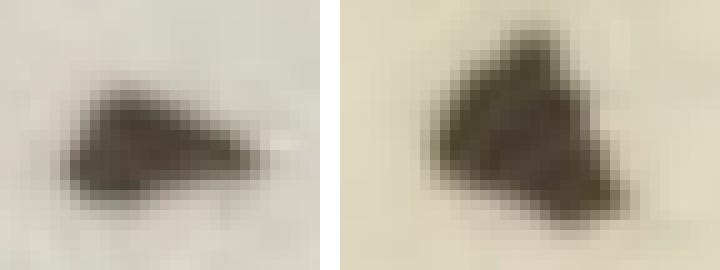

The mark at the end of line 6 in the above image is particularly short, and to my eye looks more like a full stop; I guess that its transcription as a dash is a judgement based on consistency with both the surrounding lines and most of Dickinson’s other poems.

Sometimes a mark is transcribed as a full stop; here is a zoomed comparison between one of these (right) and the very short dash above (left):

Paul Crumbley, in Inflections of the Pen: Dash and Voice in Emily Dickinson, argues that different Dickinson dashes carry meaning, and renders dashes as varying in length, height, and angle. He ambitiously interprets four distinct dash types in the above poem:

I cannot endorse such dashography.

“My Business but a Life I left / Was such remaining there?”

Reading this collection has been a positive experience. Most of the poems are quite short and fit easily into a page; if one is forgettable, then I can quickly move forward and set about forgetting it. There is plenty to relaxedly enjoy, and enough stylistic consistency that the whole feels weightier than its parts; I feel like I’m sampling from one giant work.

I Years had been from Home

And now before the Door

I dared not enter, lest a Face

I never saw beforeStare stolid into mine

And ask my Business there –

“My Business but a Life I left

Was such remaining there?”

In those stanzas the first lines are an iamb shorter than common meter, and the full four-foot third lines close the stanzas with an increase in tempo.

My final excerpt does likewise. I Googled once and have since forgotten what it means, but I won’t worry about it:

Yet interdict – my Blossom –

And abrogate – my Bee –

Lest Noon in Everlasting Night –

Drop Gabriel – and Me –

Higgledy piggledy –

Emily Dickinson –

Wrote in seclusion – her

Verses alive –

Sharing results of her

Thanatological

Studies – with Us – as she

Lies in her – Grave –

Strictly speaking, a 6 on a 1-7 scale.

I must be clear that despite using the Houghton Library’s scans, I am not taking Harvard’s side in the sordid affair which has been diminishing faith in humanity for over a century, and in which Harvard University Press is today the chief villain. HUP claims copyright on the text of all poems and letters written by Emily Dickinson.

My favourite prior art in the field of Emily Dickinson double dactyls is by Wendy Cope, who included Emily Dickinson in her 1986 collection Making Cocoa for Kingsley Amis:

Higgledy-piggledy

Emily Dickinson

Liked to use dashes

Instead of full stops.Nowadays, faced with such

Idiosyncrasy,

Critics and editors

Send for the cops.

Not that 19th-century editors were too keen on Dickinson’s dashes either! (And speaking of punctuation: I feel a comforting familiarity as I read the UK term ‘full stop’ instead of the US ‘period’, and a slight incongruity at seeing it in reference to an American’s writing.)

When I compare my attempts at light verse to those of better poets, I find that mine usually lack the creative playfulness that makes their rhymes sparkle. When I wrote for the UQ physics club’s poetry nights, it was usually sufficient to write about a technical topic – equations turned into metrical rhyme would usually get a laugh from that crowd, whether the setup was smooth or deliberately unsubtle.

Physics in verse form is inherently playful and unexpected; for more ordinary subject matter, meter and rhyme on their own are not sufficient, and you have to do some work to make the lines amusing. “Send for the cops” – I would not think of something like this.

My introductory double dactyl in this post has flaws in addition to insufficient humour. I intend the first stanza to be read literally as Dickinson not being famous in her lifetime, but instead it comes across as litotic; and the primary and secondary stress in the final line are inverted – these poems should end with a strongly stressed rhyme for greatest impact, and instead posthumous requires primary stress for the sentence to make sense. Offsetting the latter point somewhat is that lines 4 and 8 are very richly rhymed, even if the effect is subtle.

The first Dickinson double dactyl was presumably the one by Donald Hall in 1967’s Jiggery-Pokery: A Compendium of Double Dactyls, given the title Higgledy Higginson?:

Higgledy-piggledy

Emily Dickinson

Flew to the cupola

Where she could write:“Though it’s a bore I am

Heterosexual:

Murder and incest are

Sweetness and light.”

Lines 5 and 6 are historically dubious.

I continue to try asking AI to write light verse for me; Claude Opus 4.6 is the most impressive model I’ve used, producing flashier turns of phrase than I would think of. Maybe they’re the “eyeball kicks” that nostalgebraist wrote about in his discussion of LLM creative writing, and fall apart on closer inspection, but style can make up for some lack of substance in throwaway stanzas. If you pronounce a schwa between the ‘p’ and ‘r’ in line 5 here, then Claude gives a much better first impression than I do:

Higgledy-piggledy,

Emily Dickinson

Dabbled in Death—and the

Buzz of a Fly—Temperamentally

Slant in her Solitude,

Stitching the Infinite

Into a Sigh.

Very entertaining - thanks!

Excellent writing, I didn't know you had it in you.

Thank you Dave.